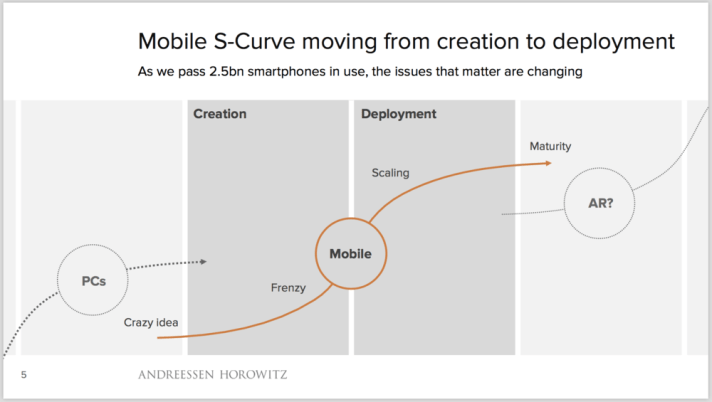

With the saturation of smartphone adoption in the developed countries and soon developing countries, I think it’s worth noting what has already happened and will likely continue to happen when it comes to the pricing of goods and services. The rise of, and there of, the hockey stick like adoption curve of smartphones have essentially lower the transaction costs for consumers alike. Smartphones serves as as the protocol layer in which other value-adds and products can be build upon them i.e. Expedia, Uber, Instacart etc.

*I have included below why this is important when it comes to crafting defensive and offensive moat for your startup’s product strategy.

Users and service and product providers can find each other more easily through their smartphones, thereby, increasing opportunities, opportunity to price compare a potential purchase from Vendor A with another potential purchase from Vendor B. The impact of the pricing due to this comparative pricing, which in great was accelerated by the adoption of smartphone. It’s not like we as consumers can’t compare prices before, but we mainly do it via the personal computer, which from the usage frequency gives it’s relative physical inconvenience, creates limitations that dampens such effects.

Pricing Compression and Consumer-Perceived Utility

But NOT all industries will go through this product pricing compression. The “utility” or at least the consumer-perceived “utility” of the specific product and/or service dedicates how deep of a pricing compression the industry and/or the product has and will continue to face. I will present some thoughts on the industries created throughout the decades.

PC – Price Compression

Take the PC industry as an example. In the early-mid 90’s, the PC essentially allows the consumers to reach and consume content (starting with file sharing + collaboration) soon that value-add spread to consumer commerce (e-commerce in the late 90’s). Utility for the consumer was therefore exponential, or somewhat inversely correlated with the price of the product.

But as we venture into the mid-late 00′, the consumer’s incremental utility of the PC started to plateau. Bear in mind we are referring to that from the consumer product’s perspective (B2B could have a different pricing implication as utility is perceived slightly different for businesses vs. that for consumers) The plateauing of the incremental utility of PC for the consumers essentially puts further downward pressure on price of PC.

Taxi – Strong Price Compression

Take Taxi industry as an example. The taxi industry have long maintained a very strong regional monopoly (most of the time, it’s duopoly) whether it be the ones in NYC, Taipei, Frankfurt, Shanghai or Tokyo. It was like this until Uber and Lyft came along. The majority, if not an overwhelming majority, of Uber and Lyft’s booking happens on the mobile phone. Let’s not forget the majority of the line items that would be in a regular business’ COGS (raw material / cars, car depreciation) section of the P&L is no longer available in their business model. These costs are essentially shifted to the driver’s themselves, which has a self-motivated incentives to absorb these costs, both knowingly or perhaps, unknowingly.

The incremental utility of taking a Uber / Lyft vs. taking a regular taxi cab is very subtle. I am referring to pure utility or perceived utility of such service rather, and not the price monetary difference.

Hotels – Weak Price Compression

Expedia and airlines have launched their mobile app booking engine for some years now, which has essentially allow more ease of price comparison for the consumers. But you might wonder WHY price compression have yet to hit this industry?

For one, most people still prefer to book their personal and business trips via the PC, perhaps in great part due to the relatively larger ticket item. But companies like HotelTonight and Airbnb have put more effort on their mobile adoption initiatives, but we have yet to see a deflation of pricing in this industry across all price and sub-verticals (boutique, bed-and-breakfast, hostels, chain hotels etc.)

The consumer utility, and thereof, incremental utility of Hotel A at a $50-100 price range versus that of Hotel B at $150-200 range varies greatly. Moreover, the consumer’s utility or perceived utility of this hotel product / service comes with heavy fragmentation. The heavy fragmentation makes it unlikely that the industry or sub-industry will go through potential heavy price compression in the medium-term.

All is all, if the incremental utility of your product and/or service along with the market dynamics at work is high, then the probability of your product going through a pricing compression in the short-medium term is pretty low. According to the The High Growth Handbook, which is totally worth a read, stated that “price determines whether you have a moat”. This is actually an inverse of most of our logic on pricing the product as affordable as possible in order to capture the greatest consumer base, which these two variables are at times not interconnected. They say good books are meant to be read one, but great books, especially one with great utility, are meant to be re-read several times.

When it comes to building defensive and offensive moat and strategies around your product, it worth noting the current price and the market dynamics at play per the above and also where it will be in the short-medium term. There are different ways to build “justification” into your pricing as your scale up, most do it by adding more product features. But the question we have to be conscious of if will this specific product feature add add substantially incremental utility to the consumers?

“Raising prices is a great way to flesh out whether you actually do have a moat… The definition of a moat is the ability to charge more.”